Stop making a Mock<things>

I don’t like mocks anymore. I used them heavily in the past, but now that I’ve moved away from this approach, my tests have become a lot better. In this post, I hope to convince you to do the same. In a future post, i’ll describe better ways to test.

TLDR;

Don’t rely on Mocking libraries. Reliance on mocking libraries causes:

- increased coupling between classes.

- reduced readability of your tests.

- reduced maintainability of your application.

Don’t blindly declare interfaces on every class. Introduce abstractions when you need them, not as a reflex.

Do:

- Design your classes and components so that truely external dependencies can be isolated.

- When needed, write hand crafted test doubles to simulate dependencies like external services.

Consider this: Can you refactor your code without having to make changes to your tests? If not, you’re in trouble.

So, stop making a Mock of things and you’ll be better off.

Background: I see mocks everywhere

Part of my job is reviewing code written by other teams. As a (primarily) .Net developer, that means reading a lot of c# code. It’s clear that many developers have become familiar with Test Driven Development, which is of course a good development. However, I’m finding that the .Net Community uses Mocking a lot, using libraries like FakeItEasy, Moq, NSubstitute or one of the many other frameworks.

What I typically see is:

- The Single Responsibility principle is followed religiously, so there are a lot of smaller classes.

- Most classes have interfaces (dto’s the obvious exception), but there’s only a single implementation in the codebase.

- Each is wrapped in it’s own unit test.

- Each dependency is mocked out in the unit tests.

These developers clearly think they are getting a lot of benefits from writing tests so they use their good intentions to spend a lot of energy to write tests that don’t nearly provide them as much benefits as they would have hoped.

This is the way

When I challenge this mocking approach, I get a lot of push-back: “A unit has to be a class”. “If you don’t isolate the class, you’re testing things twice”. “This is the only way(tm)”. “You must isolate a class, otherwise you’re doing integration testing”.

The thing is, it wasn’t always like this. This post from Martin Fowler describes that classical TDD didn’t used to rely on mocking.

The classical TDD style is to use real objects if possible and a double if it’s awkward to use the real thing. So a classical TDDer would use a real warehouse and a double for the mail service. The kind of double doesn’t really matter that much.

A mockist TDD practitioner, however, will always use a mock for any object with interesting behavior. In this case for both the warehouse and the mail service

Somewhere down the line, the practice of testing units in isolation, was translated to testing classes in isolation and mocking the rest, facilitated by mocking frameworks. I’ll do my best to describe the problems I’m seeing with this ‘mockist’ approach to testing and show alternatives to them.

The problems with mocking libraries

My biggest problems with the usage of mocking libraries are:

- You’re increasing coupling, which limits your ability to refactor.

- You’re testing the internals of your class, limiting your possibilities to refactor.

- A mock has to simulate the behavior of your class, so you have to implement some logic twice.

I’ll go into these points more below.

Decreased maintainability due to Increased coupling

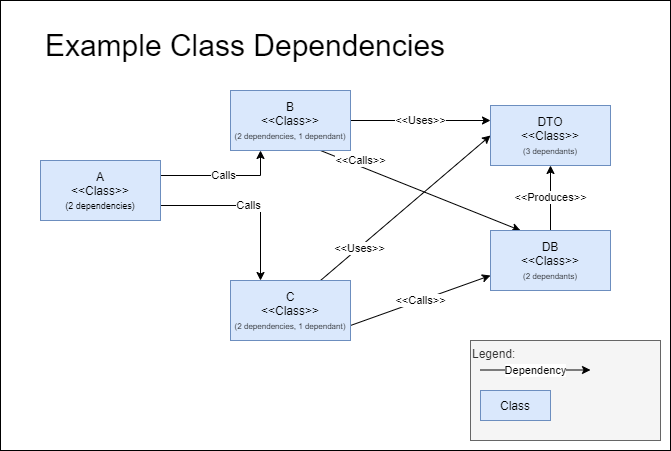

Using mocking libraries dramatically increases the number of dependencies a class has. Consider the following diagram.

.

.

It’s a fairly straightforward set of classes. Class A depends on Class B and C, which in their turn depend on Class DB and class DTO. Intentionally, there is no functional description to these classes, but you could think of class A being a controller, Class B and C providing some form of business logic and Class DB providing Database Access and Class DTO being a data transfer object.

The number of dependencies is fairly low. This makes refactoring a lot easier. Consider:

- A change to class DB. It will likely impact class B and C.

- A refactoring where parts the logic of B and C can be re-used and will be factored in a separate class. This impacts B and C and likely also A.

The obvious consequence of this approach is, that, if you change the signature of your class, you’ll also have to change all classes that use the signature.

THe non-obvious consequence of this approach, is that in order to create good mocks, you’ll also need to know a little bit about the runtime behavior of the classes being mocked. Not everything can be read from the signature. What data is being returned? In which order? What kind of validation rules are being performed by the class calling your method?

So, if you don’t rely on mocks, you end up with a much decreased maintenance burden.

Refuctoring (having to change your tests when you refactor your solution)

When relying on mocks, you have to create a good test double for the actual logic. This means that your test has to actually have to know deeply about the internal logic of your class. Any change to the internals of your class means a change to your tests. This is known as a ‘refuctor’ (a term coined by Greg Young as far as I know).

Your test is your safety net while doing changes. Making changes to your safety net when you need to rely on it is not a very good idea.

So how do we prevent that? Don’t mock your implementation, but where possible rely on the real implementation (more on that below.)

Hard to understand test tests.

The arrange-act-assert pattern of tests is often used in conjunction with mocking and SRP. So badly, that I often see people adding comments to show which bit of the test actually is part of arranging / acting / asserting. Shouldn’t that be clear from the actual code, rather than the tests?

In the arrange step, you set up your mocks. Often, specific tests have specialized setup requirements. So, each mock setup is every so slightly different. But, because you have to mock out every interaction, it’s not clear if a specific interaction is there ‘just because(tm)’ or if it’s actually significant for your tests.

Then you have an act phase. This is usually the best part of your tests. The thing that’s really important. But it’s buried in the rest of your test. So you have to put a //act comment above it just to call out where it is.

Then there is the assert. Sometimes you see big lists of assertions, but also often a Mock.Verify(). When you first read this test, you have NO idea what’s actually being verified. Then you have to look back to see what’s going on, adding to the overall confusion.

What’s a better approach to this? The Given-When-Then pattern usually makes much more readable tests. Given a certain state, when you perform an action, you observe the following results.

This focusses much more on the functionality (What the system is supposed to do), rather than on the implementation details (How the system is actually performing it).

To compare and contrast, I’ve created two solutions in the same repo:

https://github.com/Erwinvandervalk/Examples.Testing.Corona

One application is written using mocking, the other is not.

Compare the following test that uses mocking with the one below without:

[Fact]

public async Task When_saving_new_appointment_then_save_is_invoked()

{

// Arrange

var repository = A.Fake<ICoronaTestRepository>();

var dateTimeProvider = A.Fake<IDateTimeProvider>();

var now = new DateTimeOffset(2000, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, TimeSpan.FromHours(6));

A.CallTo(() => dateTimeProvider.GetNow()).Returns(now);

var sut = new ScheduleTestAppointmentCommandHandler(

repository,

dateTimeProvider);

var scheduleTestAppointmentCommand = new ScheduleTestAppointmentCommand()

{

Location = "testlocation",

ScheduledOn = now,

TestSubjectIdentificatieNummer = "number",

TestSubjectName = "name"

};

// Act

await sut.Handle(scheduleTestAppointmentCommand, CancellationToken.None);

// Assert

A.CallTo(() => repository.SaveAsync(A<CoronaTestEntity>.That.Matches(c =>

c.TestSubjectName ==

scheduleTestAppointmentCommand.TestSubjectName

&& c.TestSubjectIdentificatieNummer ==

scheduleTestAppointmentCommand.TestSubjectIdentificatieNummer

&& c.Location == scheduleTestAppointmentCommand.Location

&& c.ScheduledOn == now

&& c.CreatedOn == now

)

, CancellationToken.None))

.MustHaveHappened();

}

In this test, I have to set up several mocks, then verify that the right call to save the data actually happened. But reading this, I have questions:

- What does datetime actually have to do with the test? Is the current time important? It may be, it may not be.

- What is this ‘CoronaTestEntity’? Why is it important here?

- Have I verified every property on the corona test entity? Is it ok now?

The actual logic (calling the command) is hidden between the setup and assertion.

And, if you have to make changes (for example, change the repository signature), you have to get ready for a LOT of changes. Yes, you could probably write this better, but this example closely follows what I see in the wild.

Contrast that with the following:

[Fact]

public async Task Can_schedule_appointment()

{

var request = Some.ScheduleTestRequest();

var expectedResponse = Some.GetScheduledTestResponse();

await CoronaTestClient.ScheduleTest(

request: request,

expectedStatusCode: HttpStatusCode.OK);

var (response, result) = await CoronaTestClient.GetTest(The.TestId);

result.ShouldBeEquivalentTo(expectedResponse);

}

This test works at the api boundary (though it would have worked equally well at the command / query layer). The test only cares about the things the end user cares about. When you do X, you can observe Y. Anything else is not important for this test.

No, this is not an integration test, because I’m testing a single boundary here. Any external dependencies (such

the e-mail sending in this example). And as for databases? If the test doesn’t slow you down too much, I would

encourage you to include them in your tests. Otherwise, create a stub at the absolute lowest level.

Single Responsibility Principle causes harm here

Bob Martin coined the SOLID Principles, with the Single Responsibility Principle being the one people remember the best.

This principle leads you to create small classes, each with their own little responsibility. This means we’re breaking up the functional problem we’re trying to solve and splitting it into smaller classes. While there is something to be said for this (but please people, within reason, don’t push it to the extreme), it has some serious drawbacks when you combine it with writing tests PER Class:

Your business logic is spread across multiple classes, so the tests that verify them are also scattered.

For example:

- Input validation (IE: is a field of the right type?) is usually done where you map the request to your model. For example in the controllers.

- Business rule validation is often done in a domain layer

- With the exception of validation rules that are easier / better to do in the database. For example, duplicate constraints can very easily be handled in the database in a transactional fashion. Trying to do this in the business layer means you’re going to have

- Some validations cannot (or shouldn’t) be done transactionally, but are actually part of an asynchronous business process.

In an ideal world, you can look at the tests to get a good understanding of the functionality and rules of the system. When each test only covers a single class, and each class only covers a small part of the functionality, it becomes really hard to get a good overview of the system.

I don’t have a big problem with SOLID when applied sanely. However, I’m finding that people really go overboard. Then couple that with going overboard with using mocks and you really set yourself up for trouble.

Anyway, I favor CUPID over SOLID any time.

Conclusion

In this post, I’ve highlighted the issues I have with the use of mocking. As this post has become too long already I’ll post this now and try to focus on what you can do to avoid mocking libraries in a future post.

But hey, don’t take my word for it: